by David Izu

On Father’s Day, a son reflects on his dad’s legacy, including a black box: both literal and figurative.

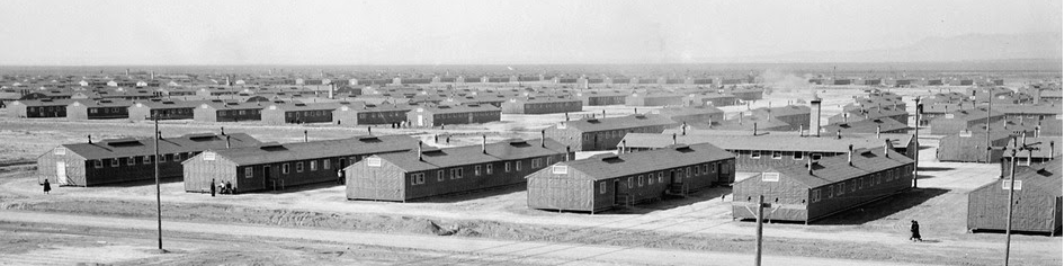

My father was still a stick-thin kid of 18 on a multi-year military-mandated “relocation” from both his California home and his civil rights as a citizen when he was drafted. He was part of a three-family caravan of related Japanese Americans who had hastily fled the West Coast, narrowly avoiding incarceration in an ethnic confinement camp.