by Ruth Sasaki

Americanism is not a matter of race or creed, it is a matter of the heart.

–Harry S. Truman

In a recent conversation with two Topaz survivors, as so often happens, the talk drifted to a family both had known in Berkeley before the War. One mentioned one of the sons–“John”–and added wistfully, “He was so handsome!” Then there was a pause.

In my childhood, such silences were respected, the talk allowed to continue on a different subject. And that’s why so many of us grew up knowing so little about our families’ lives before 1945.

This Veterans Day, we share the story of John Yukiharu Harano. Many thanks to the Sons and Daughters of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team for their efforts to preserve the stories of Nisei WWII veterans.

John Harano was born in Berkeley in 1924 to a large family. He had five brothers and three sisters; John was in the middle. He went through the Berkeley public school system (McKinley, LeConte, Willard), played basketball, and was active in the Boy Scouts Troop 26. He was the kind of young man who was selected to participate in a Boy Scout leadership conference.

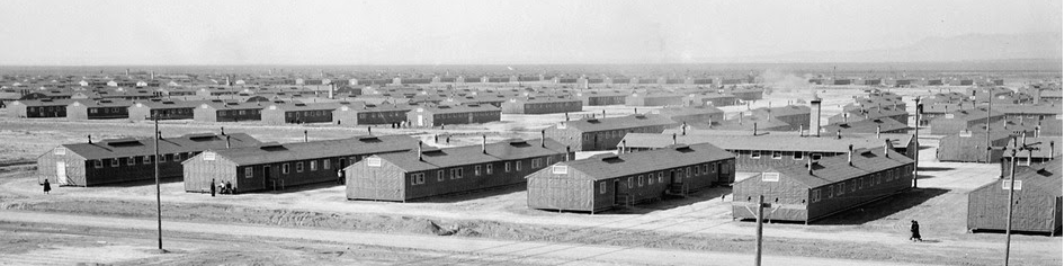

John was set to graduate from Berkeley High in June 1942. Instead, along with his parents, younger brother, Roy, eldest brother George and family, and almost all the other Japanese Americans living in the San Francisco Bay Area, he was incarcerated in Tanforan Assembly Center; then transferred in the fall to a concentration camp in Utah known as the Topaz Relocation Center.

Thanks for this great story. I was in troop 26 and never heard this story – it absolutely needs to be told to all the younger generations living in Berkeley today.

Thank you, Hiro. Please feel free to share the link with friends and family.

The Sons and Daughters of the 442nd RCT is gathering information about Japanese American veterans who died in WWII, from which much of the source material about John Harano’s time in the 442 was drawn. Check out their website: https://442sd.org/

John’s story is only one of many. I focused on him because I have Nisei friends who were neighbors of Mr. Harano in Topaz and they remembered John. I agree with you that it’s important to share this story and to remember the upstanding young men who were basically used as “cannon fodder” while their families were incarcerated behind barbed wire by the government they served. That so many survived, and prevailed, is only a testament to their grit and dedication, and the sacrifice of those who did not.