When we had left California, we could only take one suitcase each. Books were a luxury and usually left behind, except perhaps for the Bible or other religious materials. But some people did manage to squeeze in some books. At Tanforan, all books written in Japanese had been confiscated. Later in Topaz, when the Army no longer felt we were a threat, they returned the books. My dad helped to locate the original owners, but many were never claimed. These orphan books found a new home at the Topaz Japanese Library.

Dad began writing articles for the Rocky Shimpo, a Japanese newspaper in Denver. He wrote about camp life for readers on the outside, and mentioned the library and the need for books. He also wrote many letters, and soon Japanese books began trickling in. By the time the camp closed in 1945, the shelves were bulging.

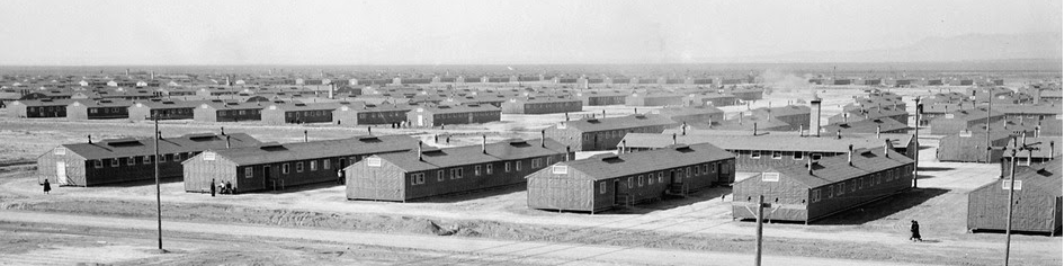

Being a bookworm, I think Dad really enjoyed this phase of his life. Upon the closing of camp, the quaint wooden “Topaz Japanese Library” sign was sent to the East Asian Library at Columbia University, where Miwa Kai, a friend of my dad’s and former Topaz resident, was working. There the sign was displayed to show that even in a wartime concentration camp in the middle of a desert, people were able to love and enjoy reading.

About the contributor: Setsuko Asano Ogami was born and raised in San Francisco until her family was sent to Tanforan and Topaz. After the War, she returned to San Francisco and graduated from George Washington High School and UC Berkeley. She then spent one year in Chicago and met her husband, Sam. They were married in SF and moved to San Mateo, CA, where they raised four children. Sets worked as a medical transcriptionist and Registrar of Mills High School in Millbrae, CA until retirement.

Copyright 2019, Setsuko Ogami. All rights reserved.