Mrs. Duveneck (Josephine) was in charge of the camp, helped by her two daughters, Liz and “Bliz” (we kids’ nickname for Hope, the elder daughter). I had my first swimming lesson there and ran races with a diverse bunch of kids. At night there was folk dancing and music.

I even got to ride a horse for the first time—it was tame, but huge, and smelled strong, so I was a little scared. When I got off after my ride, the horse took a step back and stepped on my foot. Liz was leading the riders; she heard me yell and rushed back. She tore off my shoe and sock and felt the bones. Nothing was broken, just a bruise; and I rode again the next day.

I didn’t know until many years later that Josephine Duveneck was from a Quaker background, and in addition to running the Hidden Villa camp, she and her husband were active in the American Friends’ effort to fight racial covenants in local housing. When she had the idea of a multiracial camp for kids, friends were skeptical, saying it would never work.

“It seemed to me if one could get hold of children before prejudice intervened,” she wrote, “there might be a good chance to prevent its development.”1

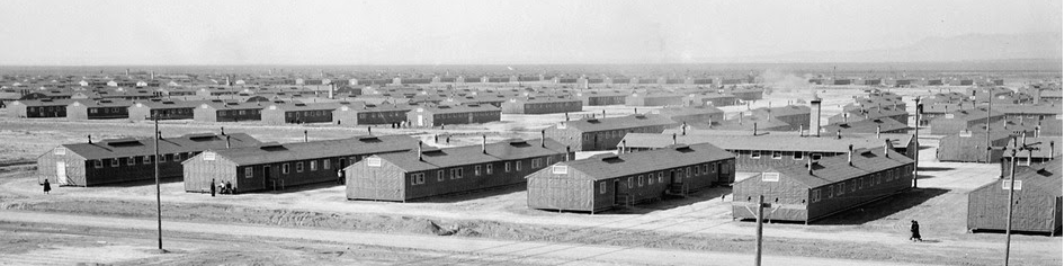

I’m now in my 80s, but I have wonderful memories of my time at Hidden Villa at a camp so different from the one where we had been incarcerated during the War that you had to wonder how the same word could apply to both. The two camps were at opposite ends of the spectrum—the products of the worst and the best aspects of human nature; and I guess it made me believe that we have a choice: we can give in to fear and hate and cause great harm to individuals, children, families; or we can choose to be like the Duvenecks—kind, visionary—and try to make the world a little better, if only by offering a brief respite in troubled times.

Note: Jon’s dad, Takeshi Yatabe, came home safely from the War in 1945. When he arrived home at 835 University Avenue in Berkeley, Liz Duveneck was visiting Jon and his mother, Kuni. She hastily excused herself and left, not wishing to intrude on the joyous family reunion. Jon’s grandfather, Kozo Yatabe, reopened the shoe repair shop that was attached to their house, and his grandmother, Rui, worked as a caregiver for a local family. Jon’s mother, Kuni, was one of the first Nisei hired by the Berkeley Unified School District, where she worked in the Payroll Department.

To learn more about the Duveneck family:

1Chapman, Robin. Defenders of the disenfranchised at Hidden Villa. Los Altos Town Crier, June 28, 2022. Accessed online 5/15/2023.

Hidden Villa/Mission & History. Hidden Villa website. Accessed 5/15/2023.

Josephine and Frank Duveneck Life, Part 2. Los Altos Hills Historical Society. Accessed 5/15/2023.

Josephine and Frank Duveneck Life, Part 1: Lost Altos Hills Historical Society. Accessed 5/15/2023.

About the contributors:

Jon Yatabe was born in Berkeley in 1937 and grew up in Redwood City, where his father (Tak Yatabe) grew flowers. He was four when his family was sent to Topaz. His father joined the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and fought in Europe. The Yatabes settled in Berkeley after the War. Jon graduated from UC Berkeley and received a Ph.D. from the University of Illinois. After a long career in Washington and the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, he retired and divides his time between Alaska and Colorado (where he loves spending time with his grandchildren).

Ruth Sasaki was born and raised in San Francisco after the War. The Takahashis, her mother’s family, were incarcerated in Tanforan and Topaz. A graduate of UC Berkeley (BA) and SF State (MA), she has lived in England and Japan. Her short story “The Loom” won the American Japanese National Literary Award, and her collection, The Loom and Other Stories, was published in 1991 by Graywolf Press. She shares her more recent writing via her website: www.rasasaki.com. Ruth volunteers as the editor and curator of the Topaz Stories Project.

Copyright 2023, Jon Yatabe and Ruth Sasaki. All rights reserved.